Award winning photo journalist, writer and documentary-maker Nick Danziger was commissioned by the Department for International Development to reveal a unique insight into changes in Afghan lives over the last five years. Through a series of individual and personal stories Behind the Headlines gets to the heart of a country often in the news but little understood by many in the UK.

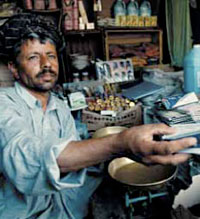

"I am sorry I’m late,” says Hayatullah apologetically, “I was trying to sort out a row between two neighbours. Their sons were fighting.” Violence is something Hayatullah is used to. His first shop was destroyed in 1983 during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

Having lost everything, Hayatullah had to labour in the fields. Several years later, he moved 200 kilometres west to the city of Mazar-e-Sharif where he opened a shop and built up the business with loans from friends. But the Taliban take-over of Mazar in 1998 saw the end to that enterprise. He moved back to Badakhshan, as a labourer in the poppy fields. “It was hard work... My health suffered.”

Having lost everything, Hayatullah had to labour in the fields. Several years later, he moved 200 kilometres west to the city of Mazar-e-Sharif where he opened a shop and built up the business with loans from friends. But the Taliban take-over of Mazar in 1998 saw the end to that enterprise. He moved back to Badakhshan, as a labourer in the poppy fields. “It was hard work... My health suffered.”

Three years ago, his luck changed. He successfully applied for a micro-credit loan of 10,000 Afghanis (£106) which allowed him to open another shop. “I promised I would not work in the poppy fields again.” Business, slow at first, now grows steadily. Hayatullah sells a wide variety of goods from rice, tea, oil, biscuits and salt to notebooks and pens... “I know what other shops charge, so I try and charge a few Afghanis less.”

He paid back his loan over two years and says his life is better than it has been for 30 years. “It is a huge difference from before: Then it was a hand-to-mouth existence. Now I can support my family; my children go to school, I can take them to the doctor and buy medicines. Without the loan, I would be waiting to die.”

Like many settlements near the main road from the Russian border to Kabul, Kart-e-sol (which means “peaceful quarter”) suffered disproportionately during the years of war and insurrection.

Now the village has three hours of electricity each evening, TV and a new access road, but a return to anarchy is still a possibility. “We try not to think about the past but fear is at the back of our minds,” says Juma Khan. “We have just rebuilt schools and roads; a return to violence would be heart-breaking.

Now the village has three hours of electricity each evening, TV and a new access road, but a return to anarchy is still a possibility. “We try not to think about the past but fear is at the back of our minds,” says Juma Khan. “We have just rebuilt schools and roads; a return to violence would be heart-breaking.

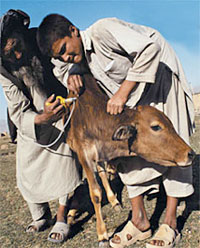

Juma Khan has more to lose than most: a mild-mannered 55-year-old shepherd with a hundred sheep, ten goats and a few cows and donkeys, he has spent most of his life with animals and was a logical choice to become the community’s veterinary worker.

The work is largely providing vaccinations, as well as undertaking castrations and treating parasitic and infectious diseases. Before taking on this job, he – like his fellow shepherds – had never consulted a vet and reckoned to lose about half his livestock a year.

In three years, this has been reduced to less than 10%.

Juma Khan learned his skills at a four-week course organised under the Afghan Government’s National Solidarity Programme and now earns about 2,500 Afghanis (£26) per month from small charges to the farmers whose animals he treats. “I am an employed person. Everyone respects me now,” he says. He can now buy medicines and support his family. He has a son who wants to be a teacher. “The old ways are disappearing and the children have very different aspirations. They don't want to be farmers or shepherds these days,” he says with a frown.

Click here for the full article (opens in a new window)